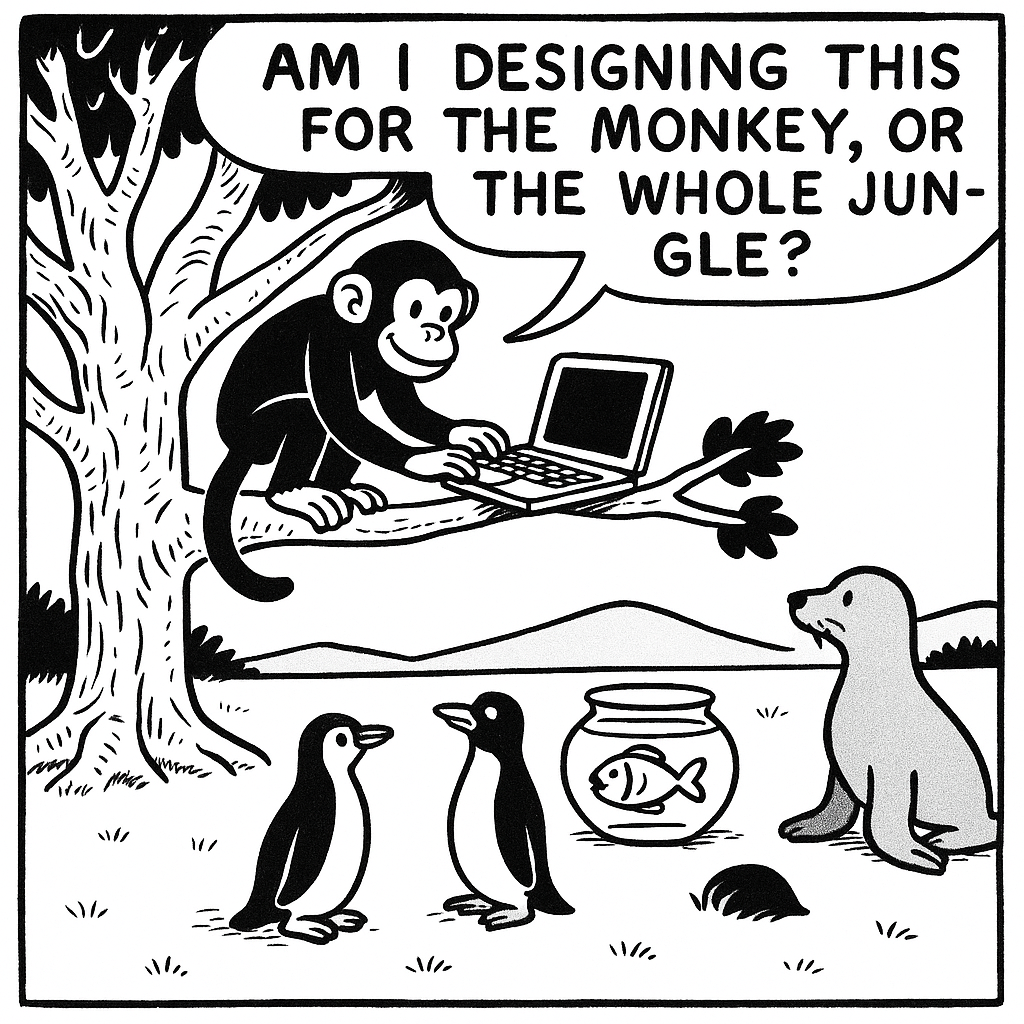

Am I Designing This for the Monkey, Or the Whole Jungle?

In instructional design, the learner is the primary stakeholder. While content and curriculum are important, it is the learner's experience that ultimately defines the success of any course. Universal Design for Learning (UDL) provides a framework that helps designers ensure that their work is student-centered, flexible, and inclusive. UDL focuses on the importance of addressing the differences in learners’ abilities, preferences, and experiences. When UDL is integrated from the beginning, it becomes a tool that empowers all learners to succeed, not just those who fit into traditional molds.

As instructional designers, our responsibility is not to design for the “average” learner, but rather for a broad spectrum of individuals. UDL helps us remove barriers before they appear. In this blog, I will explain how I integrate UDL into my design process, how I prioritize accessibility, and how I support others in creating a culture of inclusive design. This approach aligns deeply with my philosophy that learning should be accessible, equitable, and tailored for real humans with real differences.

Integrating UDL Into the Design Process

When planning a lesson, I start with the assumption that learners will come from diverse backgrounds with a wide range of needs and preferences. The UDL framework supports this assumption through its three core principles: multiple means of representation, multiple means of action and expression, and multiple means of engagement. In practice, these principles guide me to design content that can be accessed and understood in various ways, expressed through different forms, and sustained through personalized motivation.

For instance, when designing a training module on AI in agriculture, I make sure to offer written explanations, audio discussions, visual diagrams, and short videos. This allows learners to engage with the content in ways that suit their learning styles and abilities. Similarly, I provide choices for learners to demonstrate understanding; they may complete a matching game, discuss their experiences, or complete a quiz. These options do not lower standards; rather, they reflect a commitment to equitable access and meaningful learning.

Engagement is another central focus. I structure lessons to include collaborative discussions, problem-solving tasks, and real-world case studies. These activities connect with learners’ interests and make the content feel relevant. Providing opportunities for self-reflection, goal setting, and peer interaction further supports sustained engagement. UDL transforms instructional design into a creative process that values flexibility and personalization over rigid conformity.

Accessibility as a Foundation for Inclusive Learning

UDL cannot exist without accessibility. While UDL offers flexibility and personalization, accessibility ensures that learners can participate from the start. It’s not enough to make content interesting or engaging—it must be usable for all learners, including those with disabilities or cognitive differences. Accessibility considerations must be embedded throughout the course development process, not added as an afterthought.

In my design process, I ensure proper color contrast so that text is legible for those with visual impairments. I never rely on color alone to convey meaning; instead, I use patterns, labels, and icons to reinforce critical information. I add alternative text for all images and provide captions for every video. Audio content is accompanied by transcripts to support hearing-impaired learners or those who prefer reading.

I also consider learners with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), dyslexia, or autism. For them, I use a consistent layout, clear headings, and uncluttered visual designs to reduce cognitive load. I clearly note when hyperlinks open in a new tab to prevent navigation confusion. These structural details support screen reader compatibility and promote usability across devices and platforms. Accessibility is not optional—it is essential for inclusive learning environments.

Introducing UDL to Others: Building Shared Understanding

When I introduce UDL to others, I often begin with a familiar analogy. A well-known cartoon shows a monkey, elephant, fish, and bird being told to climb the same tree as a test of fairness. Predictably, the monkey excels while the others fail, not due to a lack of ability, but because the task was unfairly designed. This cartoon illustrates why traditional instruction often fails to support all learners equally. UDL offers a solution by ensuring that the way we teach is as diverse as the people we serve.

UDL is not just a set of tools; it is a mindset. When I teach others about UDL, I stress that it is not about making learning easier; it is about making it possible. I explain that UDL does not lower expectations; instead, it removes barriers that are unrelated to the actual learning goals. By proactively designing for inclusion, we avoid the need for retroactive accommodations. I also highlight the efficiency of UDL: by creating flexible pathways from the start, we reduce the need for costly redesigns or individualized interventions later on.

To make UDL practical, I share simple strategies that can be implemented immediately. These include providing captions, allowing for multiple assignment formats, and using inclusive visuals that reflect diverse identities. Once educators and teams experience the benefits of these strategies, they become more confident and committed to inclusive design. UDL becomes less of a theory and more of a natural part of the planning process.

Creating a Culture of Inclusive Design

Creating a culture of UDL requires more than individual effort. It takes leadership, consistency, and collective buy-in. I work with teams to embed UDL into course templates, planning guides, and quality checklists. We review lessons through a UDL lens, identifying areas for increased flexibility, accessibility, and representation. This process transforms design reviews into meaningful conversations about equity and learner success.

Designing for inclusion should never feel like extra work; it should feel like the right work. By normalizing UDL principles in our systems and our language, we empower others to see inclusive design not as a burden, but as a benefit. The impact reaches beyond compliance, it builds trust, belonging, and a more human-centered approach to education.

Designing for Everyone

UDL has changed the way I approach instructional design. It has taught me to see variability as a strength and to design with that variability in mind from the beginning. It has shown me that the best design is one that includes everyone, not just those who fit a predetermined mold. Integrating UDL into the design process isn’t about complexity; it’s about clarity, intention, and compassion.

Each time I design a course, I ask myself, “Am I designing this for the monkey, or the whole jungle?” This mindset drives me to create lessons that are accessible, inclusive, and empowering. Through UDL, I can make space for every learner to succeed, regardless of their background or needs. When we design for all, we elevate everyone. That is what instructional design should always aim to do.